How record collections make our identity

I don’t have a record player. I used to have my parents’ old record player, but they probably bought it in the 1980s on discount, and it didn’t work well. But I love the return to LPs as a primary physical format for music collectors.

GOOD/GRIEF by The Roseline (2020)

My friend plays guitar with the band The Roseline, and I recently purchased their new album GOOD/GRIEF on vinyl. Despite only listening to the album via Spotify, I like having the physical record around. My friend lives hundreds of miles away in my home state of Kansas, but having the album physically in my house reminds me of him and of the ways our shared musical experiences have shaped who we are today. The album cover is an image of stormy weather with a nascent tornado dropping out of the clouds, also a visual signifier of my home state thanks to The Wizard of Oz. Musically, too, the album resonates with the part of my personal musical ethic that insists beautiful music is something that is cultivated in many places and not just by music stars in “cultural metropolises.” It is produced locally in Lawrence, KS, and the influence of classic country on the album means it sounds direct and unpretentious. At the same time, I like the way the album doesn’t lull us into some retrogressive country fantasy about “back when men were men and America was great and our gasoline didn’t have biofuels in it.” There is at times a noisy and unsettled edge to the music that I like (listen to the end of “Quartz or Digital”, e.g.).

In short, the GOOD/GRIEF LP provides me a way of understanding myself, my values, and my relationships to others; it is a tool for imagining my identity. I say “imagining” identity not because identities are personal fancies, but rather to emphasize how identities—unlike vinyl record albums—are abstract. They exist in our minds and in the minds of others.

But if the answer to “who am I?” is abstract and ineffable, how does anyone have a sense of their own identity at all? Of course we do have some pre-formed and well-worn identity categories to work with (or against): national identity, gender identities, racial and ethnic identities, and so on. But does listing off how we belong to these categories really offer a complete picture of who we are? To say I am a straight white American male certainly tells you something about me, but it leaves much more unsaid.

Part of the way we cultivate the cultural and social affinities that make up our identity is through the media we consume. As rock critic and musicologist Simon Frith argues:

The experience of pop music is an experience of identity: in responding to a song, we are drawn, haphazardly, into emotional alliances with the performers and with the performers' other fans. Because of its qualities of abstractness, music is, by nature, an individualizing form. We absorb songs into our own lives and rhythm into our own bodies; they have a looseness of reference that makes them immediately accessible. At the same time, and equally significantly, music is obviously collective. We hear things as music because their sounds obey a more or less familiar cultural logic, and for most music listeners (who are not themselves music makers) this logic is out of our control.

According to Frith, music—especially popular music—functions “as identity” because it is experienced at individual and collective levels. In consuming music we are actually experiencing our identity through relationships to the music, the performers, other fans, and the cultural symbolism of the music. Identity is, then, a kind of sensory experience. We know who we are, and who others are, by using our senses to interact with a vast field of cultural products. As Frith concludes: “Music constructs our sense of identity through the direct experiences it offers of the body, time and sociability, experiences which enable us to place ourselves in imaginative cultural narratives.”

I like Frith’s thinking about identity and music because it emphasizes that identity is a process—something that is always taking shape, rather than a static unchangeable object. We are actively creating and recreating our identities, and music provides an arena in which we figure out who we are and how we relate to others.

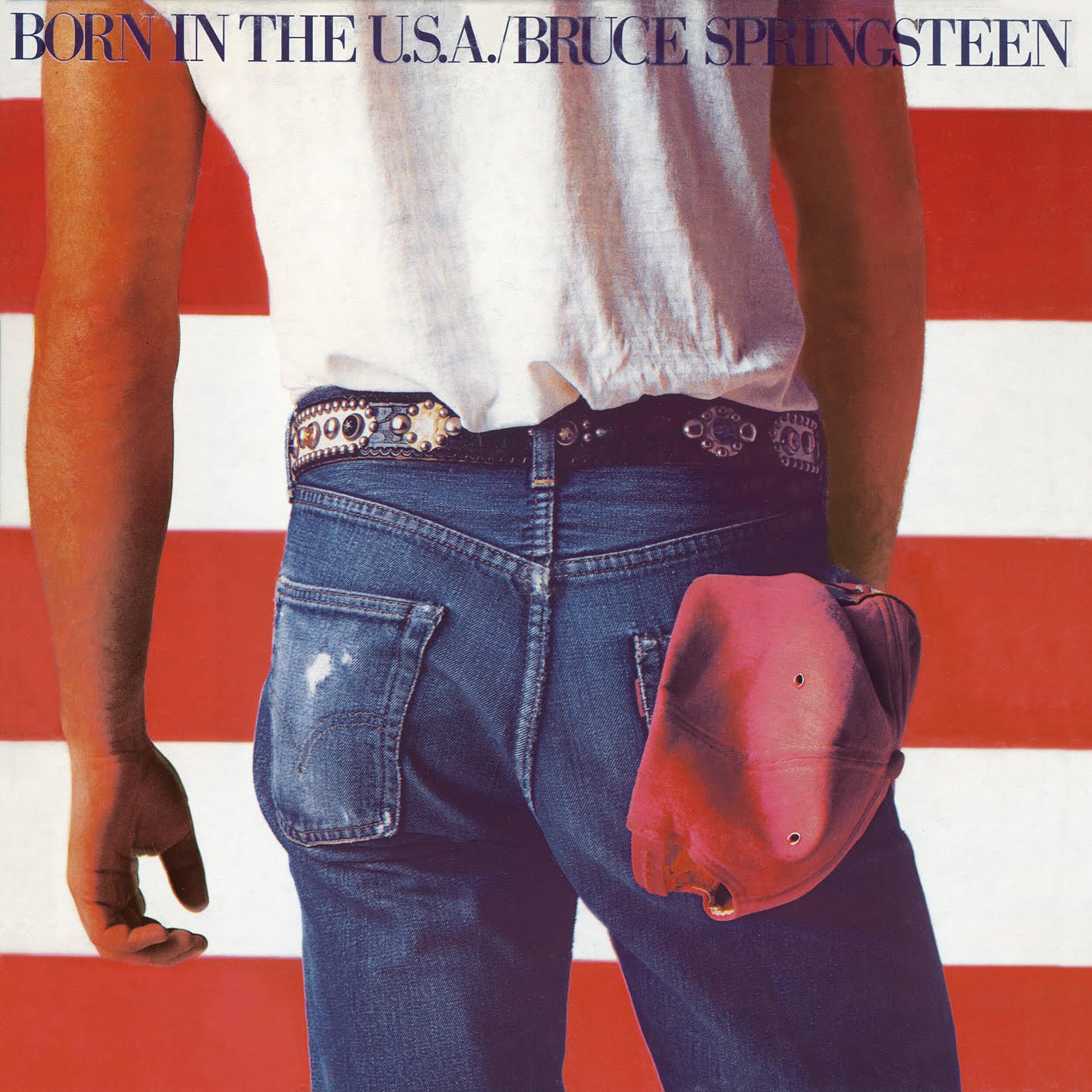

I also like the ways he uses music to think about the way we experience identity through the body, but I wonder what might be added to Frith’s conception if we expanded it to consider music audio and music visuals. If popular music provides a way of hearing and feeling our identity, it is reasonable that the album art also provides us a way of constructing identity through visual experience. And part of what makes the visual element important is that it remains even after the sounds of the music fade; it becomes a visual signifier of the social and embodied experience of music. Our record collections, whether in the form of CDs, LPs, or Spotify playlists, provide a sonic and visual mosaic that constitutes our sense of self. As we flip or swipe through these collections, our aesthetic reactions to the sights and sounds tell us who we are, who we were, and who we aspire to become.

Are you a music collector? What have you discovered about yourself through music? What does your music say about you?

***Also, as a side note, if there are smaller local groups you like, go buy their LPs and other products from them. Check to see if they have a bandcamp page. They only made enough money to cover gas before COVID-19 and they could use your support.***

Better interiors.