From Steinweiss to Spotify: Did Digital Kill Album Art?

A young Alex Steinweiss drafting an album cover.

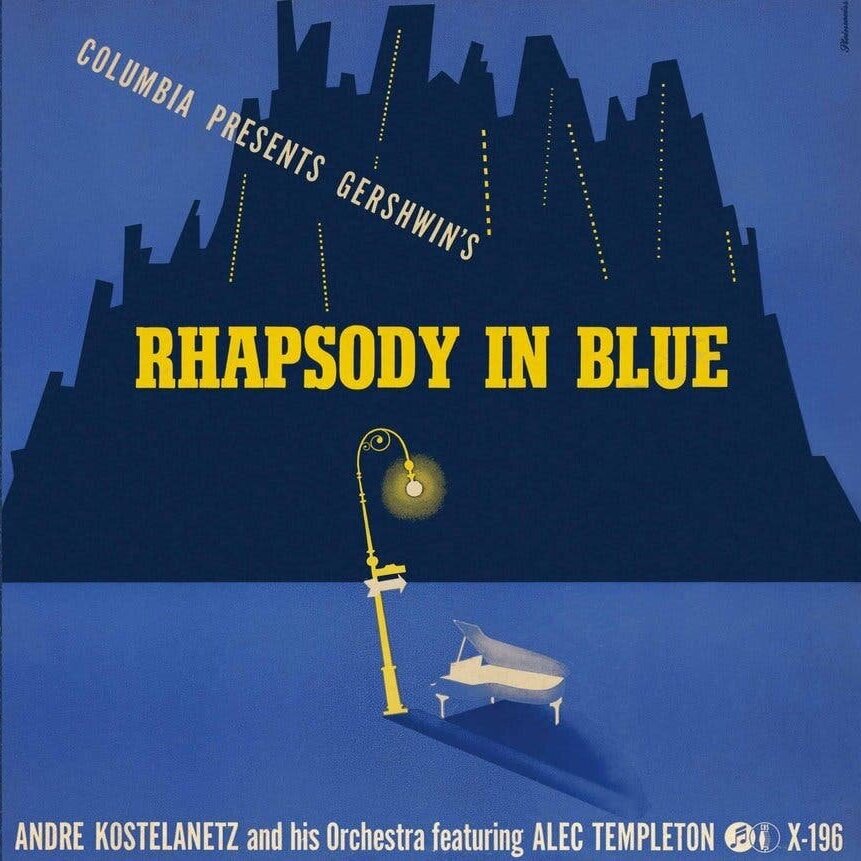

The late Alex Steinweiss, born in 1917, is typically considered the first to design album cover artwork, beginning in the late 1930s. His innovative and modernistic cover designs helped propel album sales for Columbia, where he served as art director into the 1940s. In 2000, Steinweiss and author Jennifer McKnight-Trontz teamed up to chronicle his life’s work, publishing the book For the Record: The Life and Work of Alex Steinweiss.

In the preface, Steinweiss painted a picture of himself as a design dinosaur whose most famous medium—the album cover—is essentially extinct. He reflected on a recent invitation to present at a graphic design conference, estimating the average age of those present to be around 30. He noted that a computer was the primary tool of these young conference-goers, and recalled “a general feeling of amazement that [my work] was done by hand.”

His sense that album cover art had become a thing of the past motivated his desire to do the book. He wrote, “I feel it is particularly important to devote a large portion [of the book] to record album design, as this form has ceased to exist. The development of audio cassettes and compact discs radically reduced the area of the product package that can be used for display. This dramatically curtailed the value of the album cover as a sales stimulant.”

Steinweiss, who died in 2011, would not see the full effect of the vinyl record revival that we are currently experiencing. Indeed, the years following For the Record would only seem to confirm his dismal assessment of the state of album design. In 2000, the year For the Record was published, the music industry was on the cusp of a crisis precipitated by the .mp3 and file-sharing services like Napster and Limewire. For my part—now at the age of 32—these file-sharing programs offered newfound autonomy during my musical coming of age. But this autonomy was a bit like feeling around in the dark; it offered a certain sense of excitement about what one might find, but it was also disorienting. The image-less user interfaces seemed to reduce the entire world of recorded music into a large list of filenames, devoid of the visual context and metadata that album packaging typically provided.

By 2013, the apparent triumph of digital downloads over physical formats led The New Yorker to publish a piece declaring “The End of Album Art.” The author traced a narrative of decline in album design:

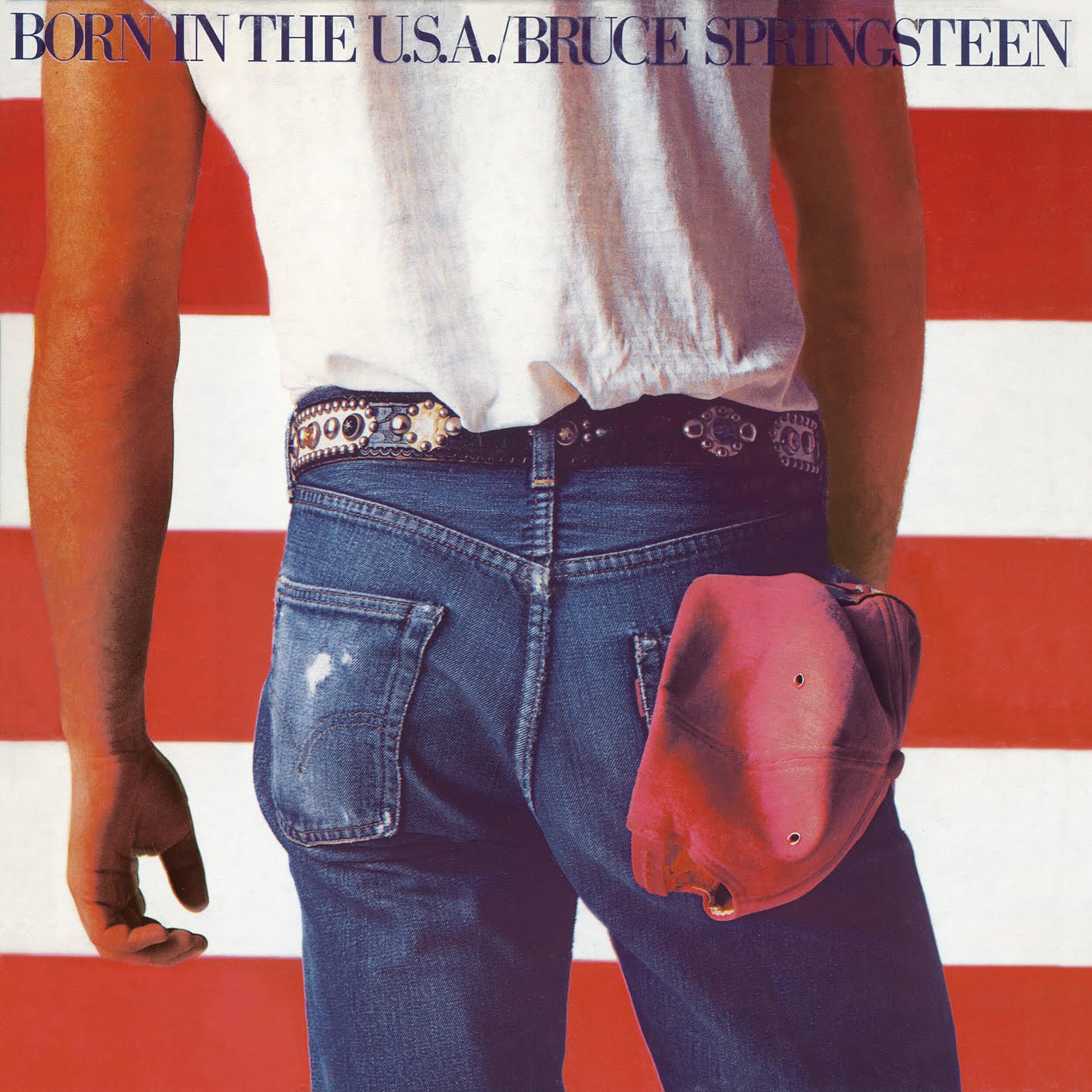

“The centrality of album design to the process of making pop music has diminished considerably over the years. The reasons are simple enough. As the LP gave way to other formats, first the cassette and then the CD, the canvas available to visual artists shrank. The CD was especially ruinous to visual creativity. … The jewel boxes … had unfriendly clear plastic covers that came from assembly lines and tabs that made it difficult to remove liner-note booklets. And the more recent move from physical products into the entirely virtual world of downloads has driven an additional, final nail into the coffin of cover art, both by deëmphasizing the album in favor of singles and by reviving the need for simple portraiture.”

It is amazing to look back at the words from Steinweiss and The New Yorker from just a decade or two away. Yes, we are now are in a new age of the revival of vinyl as the primary physical music format. But more impactful still in terms of volume has been the influence of streaming. Today it is clear that the virtual world of streaming has hardly been “a final nail in the coffin” for cover art.

To the contrary, mobile devices with high-resolution touchscreens have reintroduced mass audiences to a deeply visual way of consuming music. The streaming services in our pockets contain a seemingly bottomless library of cover art. Through the swift navigation of finger taps and swipes, users are offered endless branching possibilities of browsing, always led by visual elements. A swipe and a tap and you are viewing the covers of the entire discography of your favorite artist. Another tap, and you are seeing the cover for the latest single by a similar performer. In a few more taps, you are scrolling through the very latest releases, each track represented to your eyes and fingers by its cover art.

Not since the era of the physical record store have we used our visual sense this much to discover and navigate music collections.

Steinweiss would, no doubt, be shocked.

What favorite tracks have you discovered through their cover art? Let us know in the comments.

Better interiors.