Death and Romance: The Shared Cover Art of Classical and Metal

“Man and Woman Contemplating the Moon” oil on canvas by Caspar David Friedrich, c. 1820

In the 1990s the artwork of Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840) was found on the covers of numerous albums of classical music and… extreme death metal and black metal albums.

On the surface at least, classical music and extreme forms of metal are opposed to one another. We usually think of the first as being about refined, erudite culture, and the other a celebration of darkness, death, and rage.

What does the use of Caspar David Friedrich’s works tell us about connections between these seemingly distant genres?

Friedrich is typically considered a Romantic painter. Historians use the term Romantic to refer to a period of Western culture and thought—approximately the 19th century. As you’d expect, paintings by Friedrich—a German Romantic—are often used on covers for albums of German Romantic composers: Ludwig van Beethoven, Franz Schubert, Robert Schumann, Johannes Brahms, Gustav Mahler, etc.

Freidrich’s works have been a popular choice for classical album covers for about as long as classical albums had art on the cover. But beginning in the 1990s, Friedrich’s works suddenly began to appear on albums of the relatively new, extreme genres of black metal and death metal.

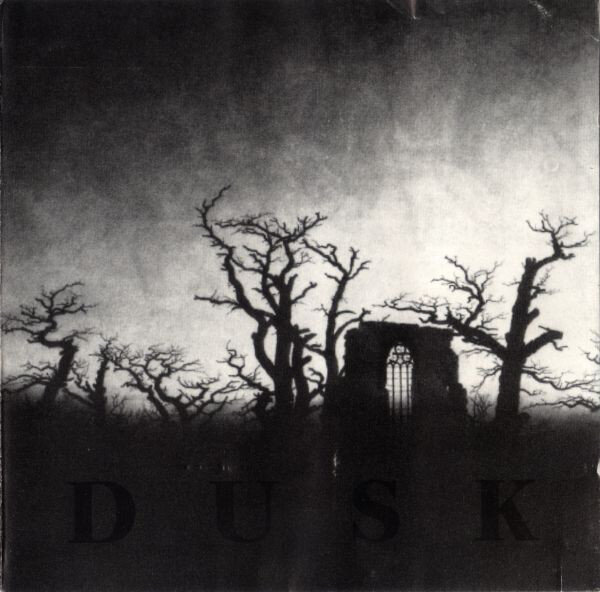

Dusk’s self titled album (Cyber Music, 1994)

Divina Enema, (Eldritch Music, 2001)

Mystic Charm’s single “Lost Empire” (Shiver Records, 1993)

These subgenres of rock trace back to “heavy metal” music which emerged in the later 1960s. Key aspects that distinguished heavy metal from earlier kinds of rock music included loudness (usually made possible by stacks of Marshall amps) and the use of a “power trio” made up of lead guitar, bass and drums (dropping the second rhythm guitarist of earlier rock band formats).

Topics of heavy metal usually centered on projecting power, whether in the form of masculine sexual prowess (like Led Zeppelin) or darker forms of power (like Black Sabbath).

During the 1980s, metal experienced a popular resurgence with bands like AC/DC, Metallica and others. It also fractured into many different subgenres. Some of these subgenres rejected mainstream popularity, and instead sought new extremes of darkness, harshness, speed, and loudness.

In brief, black metal is characterized by dark inversions of Christian symbols and ideas, and death metal by themes of—you guessed it—death and violence.

So why Friedrich for Beethoven and death metal?

Perhaps the aesthetics of Romantic classical music and extreme forms of metal are not as opposed as they might seem on the surface. In Rock and Romanticism Julian Knox argues that black metal represents a continuation of Romantic aesthetics:

“Turning away from the light and the familiar world that it illuminates, journeying through the cosmos via dreamlike introspection, courting death for the sake of art: these are concepts familiar even to audiences that have never read a single line of Romantic poetry [or, we could add, never heard to Romantic classical music], thanks in large part to the ubiquity of rock and roll music in modern popular culture.”

Friedrich’s works often captured the Romantic ethos of turning away from light and familiarity, as Knox has it--an aesthetic principle that unites many classical Romantic works and more recent death and black metal. In 1820, French Romantic composer Hector Berlioz wrote a music intended to evoke a “witches sabbath”, long before anybody had heard of black metal. Others were fascinated with composing music based on “masses for the dead” (“Requiems”). In Friedrich’s paintings we see mist, the moon, darkness, barren imposing landscapes and stone structures. Rarely do you see human faces. It is not so far fetched, then, that Friedrich’s haunting Romantic paintings would attract both metalheads and classical connoisseurs.

“Abbey in the Oakwood,” oil on canvas Caspar David Freidrich” Abby n

What do you think? Why does Friedrich’s “Abbey in the Oakwood” work both for Mahler’s Symphony no. 1 and Mystic Charm?