Sights and Sounds in the History of Black American Music (Part 3)

Integration and Beyond

Before the 1950s, widespread social segregation and racist views of Black music meant that a Black performer market appeal was limited. They might have found success on the “rhythm and blues” charts (which were designated for popular Black musical styles), but they were unlikely to score a national pop hit.

The later 50s and 60s were the age of rock ‘n’ roll, integration, and Civil Rights. Though their careers were still dogged by racism, Black rhythm and blues performers were increasingly crossing over onto the pop charts. Fats Domino, for example, reached number 10 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart with “Ain’t That a Shame” in 1955. But during this period White covers of Black rhythm and blues hits usually fared at least as well, often better. (Pat Boone’s cover of “Ain’t That A Shame” reached number 1 in 1956.)

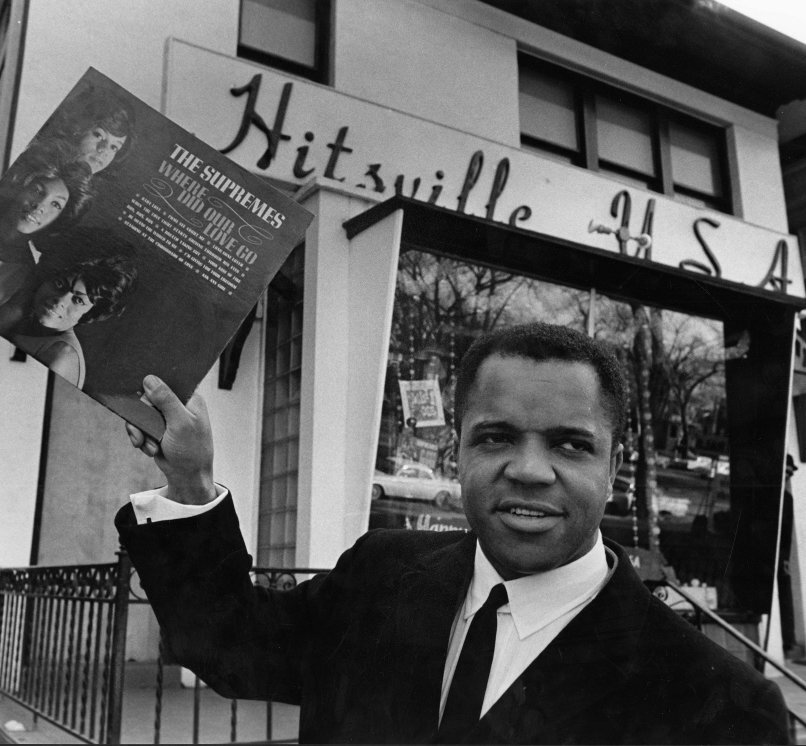

Berry Gordy in front of the Motown recording studio “Hitsville U.S.A.”, Detroit, MI.

In 1959 Berry Gordy set out to conquer the pop music world from his hometown of Detroit, establishing Motown Records. Over the next decade his Motown label would do just that, churning out hit after hit from Black performers. Part of what made Motown successful is that they developed their artists in house. From their dancing to their clothing to their table manners, everything was to be polished and well-thought-out. Below you see the 1963 promotional photo of the Marvelettes (Gladys Horton, Katherine Anderson, Georgeanna Tillman, and Wanda Young), who first reached the top of the charts for Motown with “Mr. Postman” in 1961. They all match in semi-formal dresses and neatly coiffed hair.

Motown found success in part by creating the best chance of appealing to a broad listenership, including socially conservative Whites. But as the Civil Rights Movement became more heated during the 1960s, other Black performers rejected what they saw as Eurocentric standards of beauty. For her part, the great singer Nina Simone maintained natural hair, rather than the relaxed, straightened style we see in the image of the Marvelettes. This fact features significantly in the illustration on the cover of her 1970 album Black Gold. Simone’s music rarely reached the chart-topping heights of Motown stars, but she sings unapologetically about the joy and pain of Blackness. Her music reflected a rising radicalism in the Civil Rights movement that aimed to break with White-dominated society (rather than integrating into it) and celebrate Black life by its own standards.

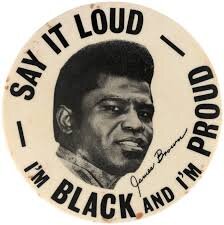

During the late 1960s and 70s, soul music became emblematic of the radical self-acceptance and political militancy of the era. The mood was, to quote James Brown: “I’m Black and I’m proud!” Others in the 1970s also sought ways to subvert dominant White symbols and aesthetics. Soul singer Isaac Hayes playfully conflated two biblical figures on his 1971 double album Black Moses. It’s clear from the cover that Hayes himself is playing the part of Black Moses. But as you open the record, it folds out into a poster-sized cross, also suggesting that Hayes is the “Black Jesus.” By connecting Hayes to this Christian religious imagery his album subverts the dominant image of White Jesus (and Moses), but it also suggests that we might find something of the divine in the sensual tracks on the album.

The 1970s also saw the rise of another genre that owes its existence to Black innovation. In New York DJs sampled popular dance beats and combined them with the semi-spoken refrains of an MC. The resulting genre came to be known as hip hop, and it became one of the most politically (and commercially) important genres of the next 40 years.

Though the roots of hip hop were in feel-good party atmospheres, during the 1980s rapping became a way to voice the plight of Black urban youth. Rapper Chuck D and hype man Flavor Flav offered a politically charged brand of hip hop as Public Enemy. Chuck D himself designed their now iconic logo. Often mistaken as a police officer in the cross hairs, the figure in the cross-hairs was intended to depict a Black hip-hopper with a hat in B-boy stance. Public Enemy’s 1988 album It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back highlighted how Black youth were targeted by the state and other forces of systemic racism.

Final thoughts:

A lot of the examples in this series have focused on Black music and performers responding to racist contexts. As Americans and as consumers of popular culture, we need to account for the fact that what is now popular (and commercially profitable) was often appropriated from the margins. Despite the fact that hip hop—among many other Black expressions—has become a mainstream musical form, we do not live in a world in which all Black lives are allowed to realize their full worth.

Nevertheless, it would be an error to represent Black music as simply a response to racism. There is deep joy, love, and beauty in its own right, as well. For that, I’ll leave you with Moses Sumney. Most of his record covers feature Sumney without a shirt. Taken alongside his music, the display of his physical form is not about masculinist toughness. Instead, the exposed skin reminds us both of the vulnerability and the sensuous pleasure of life in our bodies.